Rich countries are not raising nearly enough money to help poor nations adapt to climate change, says a report by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP).

The Adaptation Gap Report 2023, published on 2 November, shows that low-income countries are receiving between US$194 billion and $366 billion less each year than they need to cope with the growing effects of climate change, based on an analysis of 2021 financial data. The shortfall has increased by 50% since last year’s assessment, which analysed 2020 data.

“The implementation of adaptation actions is plateauing and there’s been a decline in adaptation finance,” says Henry Neufeldt, a climate researcher at the UNEP Copenhagen Climate Centre who is chief scientific editor of the report. “At the same time, we have floods, droughts and heatwaves all over the world and it’s just getting worse and worse. This newest data is a wake-up call.”

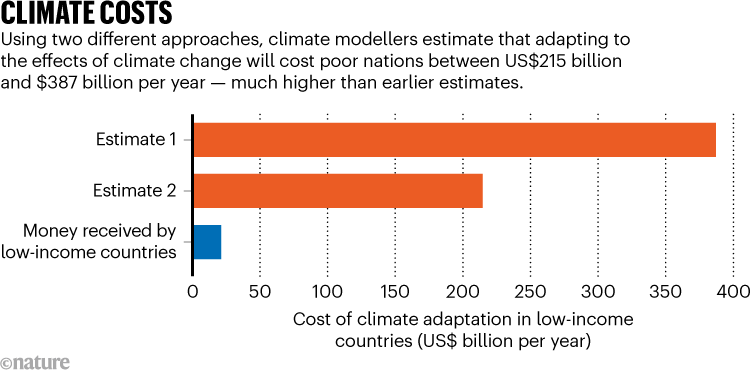

Neufeldt and his colleagues estimated that poor countries could need between $215 billion and $387 billion per year for adaptation efforts this decade. However, they received just US$21 billion from rich countries in 2021 — between one-tenth and one-eighteenth of the estimated cost (see ‘Climate costs’).

Financial pledge

Climate change is intensifying hazards such as droughts, wildfires and flooding. Many of the most vulnerable countries are also the world’s poorest, which are the least responsible for causing climate change. Under the landmark 2015 Paris climate deal, rich countries — which are most responsible for causing climate change — agreed to give poorer countries money to adapt through strategies such as growing drought-resilient crops, building sea walls to prevent flooding and setting up early-warning systems for cyclones. At the 26th UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, UK, in 2021, they pledged to double the adaptation funds, reaching $40 billion per year by 2025.

“Studies show that for every $1 billion invested in coastal flood protection, you avoid $14 billion in damages,” says Neufeldt. “If you invested $16 billion every year in agricultural adaptation, you would prevent nearly 78 million people from famine.”

The report was released ahead of the COP28 climate summit, which starts this month in the United Arab Emirates. It highlights that one in six parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has no plans, strategies or policy on climate adaptation. “Many of these are countries that are particularly vulnerable to climate impacts,” says Neufeldt.

Climate funds are financial institutions that collect pledges from nations; low-income countries can apply for money to fund their adaptation projects. The number of new adaptation projects supported by UNFCCC money, such as the Green Climate Fund, dropped from 2021 to 2022. “This is due to factors including the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and other geopolitical crises that are emerging, that put adaptation on the back burner,” says Neufeldt.

Hurdles to access

These events aside, it has always been difficult for countries to access global climate funds for adaptation, says Clare Shakya, director of strategic impact at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) in London.

The funds have a high bar to participation — they require countries to have a proven track record of using policies and practices that work, she says. “This just creates loads of barriers for small countries within governments who don’t have the bandwidth to respond to all of these demands,” she says.

Simplifying the process of accessing funds by minimizing the requirements could help money flow to the places that need it most, says Shakya.

In the meantime, it’s crucial to help low-income countries to use the money they can access effectively. That could enable them to put in place urgently needed adaptation measures, says Ritu Bharadwaj, a climate-policy researcher at the IIED.

Beyond economic and environmental benefits, closing the adaptation gap will reduce health and gender inequality.

Many of the regions most vulnerable to climate change struggle with societal issues such as the marginalization of women, children not going to school and poor sanitation. For example, in some vulnerable regions, women generally bear more responsibility than men for providing food, water and fuel. If extreme weather interferes with crops or access to water, this makes it harder for women to secure enough food or income, and increases chance that girls have to leave school to help. The climate is exacerbating these inequities, says Bharadwaj.

“There is already clear evidence that climate change is harming the health of people across the globe,” says Elizabeth Robinson, director of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment in London. “Without much greater investment in adaptation, health impacts of climate change will only get worse.”

"poor" - Google News

November 03, 2023 at 02:00PM

https://ift.tt/k18hS9x

Rich countries fall short on climate aid for poor nations - Nature.com

"poor" - Google News

https://ift.tt/ba8Fn12

https://ift.tt/aoIeqNF

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Rich countries fall short on climate aid for poor nations - Nature.com"

Post a Comment